NISUS WRITER PRO (MAC only) In Nisus Writer Pro, automatic text is linked with a glossary. A glossary, when loaded, is available for all documents, whatever template is used. The Cuneiform glossary is a file with cuneiform signs and associated entries. For more informations, see the NWP guide. Format: Cuneiform.ngloss. To OCR a PDF on Mac for free, there are 2 workarounds, either using an offline standalone MAC OCR PDF app or an online, free PDF OCR tool. Yet, we know that offline Mac OCR PDF application is seldom free, if one PDF OCR program is given for free, it must come with limited features, like LEADTOOLS OCR Application.

- Cuneiform For Mac Os

- Cuneiform For Mac Shortcut

- Cuneiform Forms

- Cuneiform For Mac Keyboard

- Cuneiform Fonts For Mac

- Decipherment of cuneiform

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

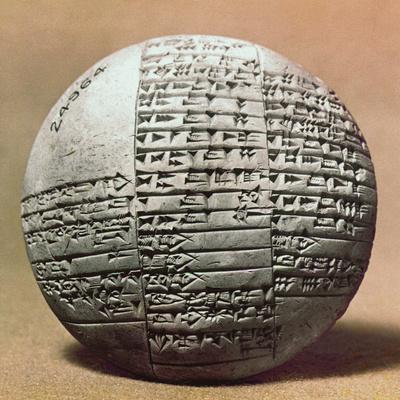

Join Britannica's Publishing Partner Program and our community of experts to gain a global audience for your work!Cuneiform, system of writing used in the ancient Middle East. The name, a coinage from Latin and Middle French roots meaning “wedge-shaped,” has been the modern designation from the early 18th century onward. Cuneiform was the most widespread and historically significant writing system in the ancient Middle East. Its active history comprised the last three millennia bce, its long development and geographic expansion involved numerous successive cultures and languages, and its overall significance as an international graphic medium of civilization is second only to that of the Phoenician-Greek-Latin alphabet.

For a table illustrating the development of cuneiform, see below.

Origin and character of cuneiform

The origins of cuneiform may be traced back approximately to the end of the 4th millennium bce. At that time the Sumerians, a people of unknown ethnic and linguistic affinities, inhabited southern Mesopotamia and the region west of the mouth of the Euphrates known as Chaldea. While it does not follow that they were the earliest inhabitants of the region or the true originators of their system of writing, it is to them that the first attested traces of cuneiform writing are conclusively assigned. The earliest written records in the Sumerian language are pictographic tablets from Uruk (Erech), evidently lists or ledgers of commodities identified by drawings of the objects and accompanied by numerals and personal names. Such word writing was able to express only the basic ideas of concrete objects. Numerical notions were easily rendered by the repetitional use of strokes or circles. However, the representation of proper names, for example, necessitated an early recourse to the rebus principle—i.e., the use of pictographic shapes to evoke in the reader’s mind an underlying sound form rather than the basic notion of the drawn object. This brought about a transition from pure word writing to a partial phonetic script. Thus, for example, the picture of a hand came to stand not only for Sumerian šu (“hand”) but also for the phonetic syllable šu in any required context. Sumerian words were largely monosyllabic, so the signs generally denoted syllables, and the resulting mixture is termed a word-syllabic script. The inventory of phonetic symbols henceforth enabled the Sumerians to denote grammatical elements by phonetic complements added to the word signs (logograms or ideograms). Because Sumerian had many identical sounding (homophonous) words, several logograms frequently yielded identical phonetic values and are distinguished in modern transliteration—(as, for example, ba, bá, bà, ba4). Because a logogram often represented several related notions with different names (e.g., “sun,” “day,” “bright”), it was capable of assuming more than one phonetic value (this feature is called polyphony).

In the course of the 3rd millennium the writing became successively more cursive, and the pictographs developed into conventionalized linear drawings. Due to the prevalent use of clay tablets as writing material (stone, metal, or wood also were employed occasionally), the linear strokes acquired a wedge-shaped appearance by being pressed into the soft clay with the slanted edge of a stylus. Curving lines disappeared from writing, and the normal order of signs was fixed as running from left to right, without any word-divider. This change from earlier columns running downward entailed turning the signs on one side.

Spread and development of cuneiform

Before these developments had been completed, the Sumerian writing system was adopted by the Akkadians, Semitic invaders who established themselves in Mesopotamia about the middle of the 3rd millennium. In adapting the script to their wholly different language, the Akkadians retained the Sumerian logograms and combinations of logograms for more complex notions but pronounced them as the corresponding Akkadian words. They also kept the phonetic values but extended them far beyond the original Sumerian inventory of simple types (open or closed syllables like ba or ab). Many more complex syllabic values of Sumerian logograms (of the type kan, mul, bat) were transferred to the phonetic level, and polyphony became an increasingly serious complication in Akkadian cuneiform (e.g., the original pictograph for “sun” may be read phonetically as ud, tam, tú, par, laḫ, ḫiš). The Akkadian readings of the logograms added new complicated values. Thus the sign for “land” or “mountain range” (originally a picture of three mountain tops) has the phonetic value kur on the basis of Sumerian but also mat and šad from Akkadian mātu (“land”) and šadû (“mountain”). No effort was made until very late to alleviate the resulting confusion, and equivalent “graphies” like ta-am and tam continued to exist side by side throughout the long history of Akkadian cuneiform.

The earliest type of Semitic cuneiform in Mesopotamia is called the Old Akkadian, seen for example in the inscriptions of the ruler Sargon of Akkad (died c. 2279 bce). Sumer, the southernmost part of the country, continued to be a loose agglomeration of independent city-states until it was united by Gudea of Lagash (died c. 2124 bce) in a last brief manifestation of specifically Sumerian culture. The political hegemony then passed decisively to the Akkadians, and King Hammurabi of Babylon (died 1750 bce) unified all of southern Mesopotamia. Babylonia thus became the great and influential centre of Mesopotamian culture. The Code of Hammurabi is written in Old Babylonian cuneiform, which developed throughout the shifting and less brilliant later eras of Babylonian history into Middle and New Babylonian types. Farther north in Mesopotamia the beginnings of Assur were humbler. Specifically Old Assyrian cuneiform is attested mostly in the records of Assyrian trading colonists in central Asia Minor (c. 1950 bce; the so-called Cappadocian tablets) and Middle Assyrian in an extensive Law Code and other documents. The Neo-Assyrian period was the great era of Assyrian power, and the writing culminated in the extensive records from the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (c. 650 bce).

The expansion of cuneiform writing outside Mesopotamia began in the 3rd millennium, when the country of Elam in southwestern Iran was in contact with Mesopotamian culture and adopted the system of writing. The Elamite sideline of cuneiform continued far into the 1st millennium bce, when it presumably provided the Indo-European Persians with the external model for creating a new simplified quasi-alphabetic cuneiform writing for the Old Persian language. The Hurrians in northern Mesopotamia and around the upper stretches of the Euphrates adopted Old Akkadian cuneiform around 2000 bce and passed it on to the Indo-European Hittites, who had invaded central Asia Minor at about that time.

In the 2nd millennium the Akkadian of Babylonia, frequently in somewhat distorted and barbarous varieties, became a lingua franca of international intercourse in the entire Middle East, and cuneiform writing thus became a universal medium of written communication. The political correspondence of the era was conducted almost exclusively in that language and writing. Cuneiform was sometimes adapted, as in the consonantal script of the Canaanite city of Ugarit on the Syrian coast (c. 1400 bce), or simply taken over, as in the inscriptions of the kingdom of Urartu or Haldi in the Armenian mountains from the 9th to 6th centuries bce; the language is remotely related to Hurrian, and the script is a borrowed variety of Neo-Assyrian cuneiform. Even after the fall of the Assyrian and Babylonian kingdoms in the 7th and 6th centuries bce, when Aramaic had become the general popular language, rather decadent varieties of Late Babylonian and Assyrian survived as written languages in cuneiform almost down to the time of Christ.

- key people

- related topics

Online Editors

Some online tools created by Gerfrid G.W. Müller might help to write transliterations or Old Babylonian cuneiform (installs cuneiform fonts first!)

I. Introduction

Unicode Standard 5.0 and cuneiform

The Unicode Standard version 5.0 (July 2006, see http://unicode.org) now includes blocks for Cuneiform (12000-1236E) and Cuneiform Numbers and Punctuation (12400-12462 and 12470-12473).

Unicode is a computer standard that assigns to each character a unique number (code point), whatever the operating system, the software and the language may be. This standard was developped during the times for many writing systems, but was lacking for Cuneiform script. Initiative for Cuneiform Encoding (ICE http://www.jhu.edu/ice/), founded in Baltimore in 2000, aimed to fill this gap. In 2006, a final proposal for the cuneiform writing system was elaborated by Steve Tinney, Michael Everson and Karljürgen Feuerherm (http://std.dkuug.dk/jtc1/sc2/wg2/docs/n2786.pdf).

The assignment of new blocks for Cuneiform has the purpose to give a solution that non-Unicode fonts could not provide. Limited to 256 characters, they do not permit the encoding of signs in a single font. Two, three, and even four fonts were necessary to have the whole set of signs for Old babylonian, Hittite or Neo-Assyrian. The encoding itself was different from one font to antoher. In this point of view, the Unicode proposal for Cuneiform would make easier the encoding and the use of the fonts. On the whole, the results are more than positive and we immediately see the advantages: electronical corpora, lexicographic databases, research on corpus (sorting, occurrences, index... see http://www.jhu.edu/ice/).

As every innovation, the Unicode Standard 5.0, even if it meets the major needs, gives rise to some difficulties and problems, which probably would need some improvements. The main critical review has been done by R. Borger in the introduction to List of Neo-Assyrian Cuneiform Signs. A practical and critical guide to the Unicode blocks «Cuneiform» and «Cuneiform Numbers» of Unicode Standard Version 5.0 (http://www.sumerisches-glossar.de/download/SignListNeoAssyrian.pdf), compiled by M. Studt (D. Bachmann's revised list). See also the article Unicode cuneiform (2007, August 24): Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicode_cuneiform).

The final proposal sets out the general principles for encoding.

1) The character inventory is based on the Ur III sign list, compiled by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. As said, this is a first stage in the definition of code points; other stages should concern other periods (Old Akkadien, 2334-2154 et Early Dynastic, 2900-2335, Archaic Cuneiform).

As Borger wrote, the proposed list is limited, in the sense that it does not account for different periods and regions using cuneiform writing. The consequence is that some signs used by Hittite or even Neo-Assyrian do not have code point for Hittite or even for Neo-Assyrian (see the lists). Several code points should be added to get a complete list, concerning all chronological and geographical aspects of cuneiform writing system.

2) Cuneiform sign and cuneiform characters do not necessarily correspond; complex signs and compound signs are distinguished (see final proposal, p. 7).

Complex signs are made up of primary sign with one or more secondary sign written within it or otherwise conjoined to it. The whole is a unit. For example, the single sign KA 𒅗 is used to form complex sign KA×GU 𒅫 (where GU is written in KA), KA×LI 𒅲 ... The complex sign being a unit, it has a specific code point, in this example, KA = U12157, KA×GU = U1216B, KA×LI = U12172.

Some signs of Borger's List in MeZL do not have code point. These are rare signs, KA×TU, KA×ḪAR, LAGAB×GI etc., about thirty, fourty signs. Others are attested for Hittite: KA×ÀŠ, KA×ÚR, KA×GAG, KA×GIŠ, KA×PA, KA×LUM, SI×SÁ, EZEN׊E, AMAR×KU₆, ÁB×A, KISIM₅×Ú-MAŠ.

Compound signs are made of two or more signs organized in linear sequences. Each sign exists in other respects as single character. The whole is generally viewed as a unit, but each component will be separately encoded. For example: IDIGNA, composed of MAŠ+GÚ+GÀR, code points U12226+U12118+U120FC 𒈦𒄘𒃼.

The Unicode Standard 5.0 list of Cuneiform signs is arranged according to the latin alphabet and gives an 'etymological' description of the signs (simple, complex and compound, see Cuneiform Unicode, Wikipedia). This list, Borger says, 'introduces new set on conventional readings, without offering any explanation', instead of known and generally used conventional readings in Assyriology. The aim is to describe the sign (Cuneiform sign A, Cuneiform sign KA times LI, etc.), but the use often is not practical (we have to know that GIR = ḪAgûnu, AMAŠ = DAG KISIM₅ times LU + plus MASH2). The most critical point of view about this new way deals with the sign analysis on the one hand, and the sometimes laborious use of code points. The 'splittability' of some signs actually seems arbitrary and could be discussed ; see for example Borger, MeZL, n° 754 MEŠ, which has to be decomposed ME+U+U+U (ME = U12228; U+U+U = U1230D) or n° 459 DUL splitted U+TÚG (U1230B+U12306) according to the Unicode Standard; but according to Borger, these signs are not really 'splittable'. In other cases, it will be necessary to combine one, two, or three code points: U12226+U12118+U120FC for IDIGNA, U12263+U121EC for TÙR (NUN-LAGAR), etc. Ligatures are in theory impossible, unless another font is made, which contains the needed variants (that could be absolutely artificial, see, for Hittite, notes with the sign lists). For Old Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian sign NIGIN (MeZL, n° 804) = LAGAB-LAGAB (U121B8+ U121B8), we get 𒆸𒆸, without the possibility of a real ligature.

In other cases, the split of signs is difficult, like for Hittite, which uses signs based on an Old Babylonian cursive from North Syria (E. Neu - C. Rüster, Hethitisches Zeichenlexikon, Wiesbaden, 1989). The sign IDIGNA, as used in Hittite syllabary, is not splittable in practice: U12226+U12118+U120FC gives 𒈦𒄘𒃼, not very like the 'real' sign 𒈦𒄘𒃼. For this kind of compound sign, we have made the resolution to isolate artificially each component, that means to design variant for MAŠ, for GÚ, for GÀR, which permit to get the final sign. This kind of variant is pointed out in the footnotes in the sign list. The use of automatic text will also permit to get round this problem (see below).

II. Cuneiform fonts: Old babylonian, neo-assyrian, hittite

The Unicode Cuneiform fonts (TTF) have been designed by Sylvie Vanséveren. They are freely available for the scientific community. They can not be altered or solded.

- Santakku: Old Babylonian, cursive script

- SantakkuM: Old Babylonian, momumental script (Hammurabi)

- Assurbanipal: Neo-Assyrian

- Ullikummi (A, B, C): Hittite.

Fonts installation

- MacOSX: put the fonts into User/Library/Fonts.

- Windows (XP): Click on Start, then Configure settings. Click on Fonts: the font folder opens.

Two ways for adding fonts in Windows:

- direct copy of fonts in the font folder

- click on File menu in the font window and choose Install new font. Select the font in the List of fonts. Click on OK.

Sign List and notes

Each sign list contains the following:- MeZL numbering

- Unicode code point

- sign (conventional reading and Unicode description)

- sign in the font (and variant for Hittite)

- autotext

Explanation notes and remarks in each list concern some specific problem about a sign, about the split of signs, and about the necessary variants for composing complex and compound signs (almost for Hittite).

Automatic Text

Once the encoding is made, it remains to use the fonts in concrete terms, that is to write in cuneiform. It always is possible to access to the signs via the Character Palette in Mac OSX or via the Special Character menu in text editor, but this method is laborious and tedious, since there is necessary to know the signs, or recognize them, or to know the code point of each specific sign. In order to make things easier, one can use automatic text.

Automatic text insertion is possible in text editors like Word and Nisus Writer Pro. File templates are given here for Word and Nisus. Each template can be modified by the user, who can add, modify or delete entries.

NB. Neo- et OpenOffice (Mac et PC) do not seem to correctly embed the fonts (nor via special character insertion, neither via Character Palette in OSX). Other text editor (like Mellel for Mac) do not offer autotext.

The principle consists in associating an automatic text entry with a sign, or group of signs. It is so possible to write in Cuneiform without having to know the code point of the signs. In order to do that, some latin characters are encoded in the fonts (characters from the Cuneitruetype font with kind permission of Prof. Dominique Charpin).

So typing for example the entry 'ma', and then select automatic insertion (via Insertion menu or keyboard shortcut, see below), we obtain the sign (U12220):

- 𒈠 (Assurbanipal)

- 𒈠 (Santakku)

- 𒈠 (SantakkuM)

- 𒈠 (UllikummiA)

In the same way, the entry 'lugal' will give (U12217)

- 𒈗 (Assurbanipal)

- 𒈗 (Santakku)

- 𒈗 (SantakkuM)

- 𒈗 (UllikummiA)

For compound signs, made of two or more signs in linear sequence, for each of which one code point is assigned, the principle permits to associate the signs:

Cuneiform For Mac Os

- 'mac' (MAŠ) U12226 𒈦 (Assurbanipal) 𒈦 (SantakkuM)

- 'gu2' (GÚ) U12118 𒄘 (Assurbanipal) 𒄘 (SantakkuM)

- 'gar3' (GÀR) U120FC 𒃼 (Assurbanipal) 𒃼 (SantakkuM)

- 'idigna' 𒈦𒄘𒃼 (Assurbanipal) 𒈦𒄘𒃼 (SantakkuM)

NB. Only one template is proposed here for Old Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian (Cuneiform.dot); the automatic entries are the same. Since Hittite regularly has other values for the signs, another template (Hittite.dot) contains the insertions based on the Hittite values.

Variants are marked with 'v' or 'vv' after the entry

- Assurbanipal: me3 𒀞 me3v 𒅠

- Ullikummi: mah 𒈤 mahv 𒈤 mahvv 𒈤

MICROSOFT WORD

For more information, see Word Help.

Template: Cuneiform.dot, Hittite.dot

Installation:

- MacOSX: Applicationsfolder Microsoft Office Templates (or in the folder My templates)

- Windows (XP): C:WindowsDocuments and SettingsUserApplication DataMicrosoftTemplates (hidden folder by default).

- Choose template via Library projects.

Use of autotext

There are two different ways to proceed:

- Insertion menu → Automatic Insertion. A rolled list gives the different insertions.

- Keyboard shortcut for automatic insertion.

To access to the dialog box for defining entry of automatic text:

- Insertion menu → Automatic Insertion (top of the rolled list)

- or click on button 'automatic insertion'

- or via Tools menu → automatic correction

Cuneiform For Mac Shortcut

To define a keyboard shortcut for the command automatic insertion: Tools menu → Customize keyboard In the dialog box, select on the left All the commands Select AutomaticInsertion and choose a keyboard shortcut.

To access to the button 'automatic insertion' Tools menu → Customize toolbar Drag the button on a toolbar (Standard toolbar for example).

Cuneiform Forms

NISUS WRITER PRO (MAC only)

In Nisus Writer Pro, automatic text is linked with a glossary. A glossary, when loaded, is available for all documents, whatever template is used. The Cuneiform glossary is a file with cuneiform signs and associated entries. For more informations, see the NWP guide. Format: Cuneiform.ngloss Installation: User/Library/Application Support/Nisus/Glossaries the glossary can be imported via Preferences → Quickfix → Import glossary (choose Cuneiform.ngloss).

Cuneiform For Mac Keyboard

Use of glossary

Cuneiform Fonts For Mac

- Enter the text entry

- Entries are expanded in Edit menu → expand glossary entries

- Glossary entries can also be expanded manually with a combination key (⌘D)

- You can also choose 'Automatic expansion of glossary entries as you type' in Preferences → Quickfix

- To add, delete, or modify glossary entries, open Cuneiform.ngloss and proceed. Each entry must be separated by a Glossary entry break (Insert menu). Save the file.